Dance, Camera, Dance: Directorial Choreography in the Live Anthology Drama

Live television is not the most popular topic among video essay makers. (Prestige television series are more in vogue, as is clear from their dominance among the videos in our Television Dossier). If a video essayist does tackle live tv, they often focus on either newscasts or on popular sports or entertainment programs.

This great piece published in MOVIE: A Journal of Film Criticism fills part of that void. Peter Labuza takes an in-depth look at the live dramatic anthology programs that were the crown jewels of television’s first Golden Age in the 1950s. As Labuza writes in his concise creator’s statement, his focus is not on the writers or actors of those live programs: instead he “examines the production methods of 1950s live television and the director’s role in shaping visual style”. The directors that feature in his video essay are familiar names, because famed helmers such as John Frankenheimer, Delbert Mann and Sidney Lumet started off in live tv. Only later would they take the stylistic skills and the production methods they honed there to Hollywood.

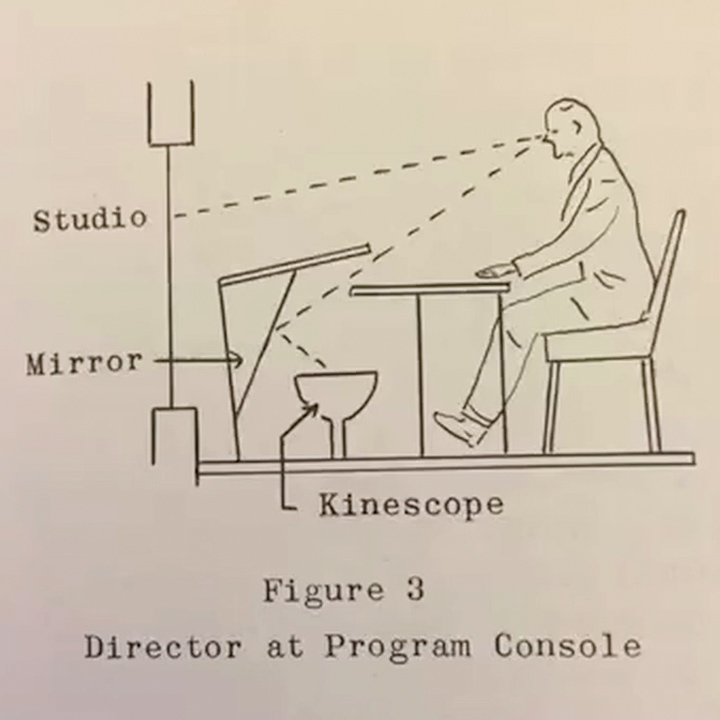

Labuza’s video essay is jam-packed with historical information and keen insights: it serves as a crash course in this particular form of television making. His focus on the role of directors is akin to the auteur theory discourse in film studies, with its emphasis on mise-en-scène as the hallmark of directorial style. Where this piece excels is in its inventive reverse-engineering of the movements of the television cameras during a live broadcast. Labuza takes a floor plan of the soundstage of one particular live broadcast (A Town Has Turned to Dust), adds the positions of the cameras and the actors, and then animates all these elements. The resulting abstracted top-down view reveals the intricate choreography of the performers in front and behind the cameras: they are engaged in a veritable dance (that gave the video essay its title).

Labuza shows how the television directors shifted constantly between a ground level view (the cameras) and one from above, which helped shape their formal choices. This calls to mind the ballets de cour (“court ballets”) in Italy and France in the 16th and 17th centuries. Those performances were choreographed to be viewed from overhead – the spectators were on balconies surrounding the dance floor – and the dancing therefore stressed geometric patterns.

The influence of these ballets is obvious in Busby Berkeley’s ornate choreographies, but one might argue that the live television director of the 1950s, because of his similarly high vantage point, also was inspired to intricately choreograph his performers and cameras.

Peter Labuza asks us to think of these live television programs as being “directed from above”. He successfully argues that this unique viewpoint influenced the aesthetic choices the directors made, and his great video essay opens up new perspectives for us, the viewer, as well.