Desktop Documentary

When travelling, I have always sought out and visited the homes of famous writers.

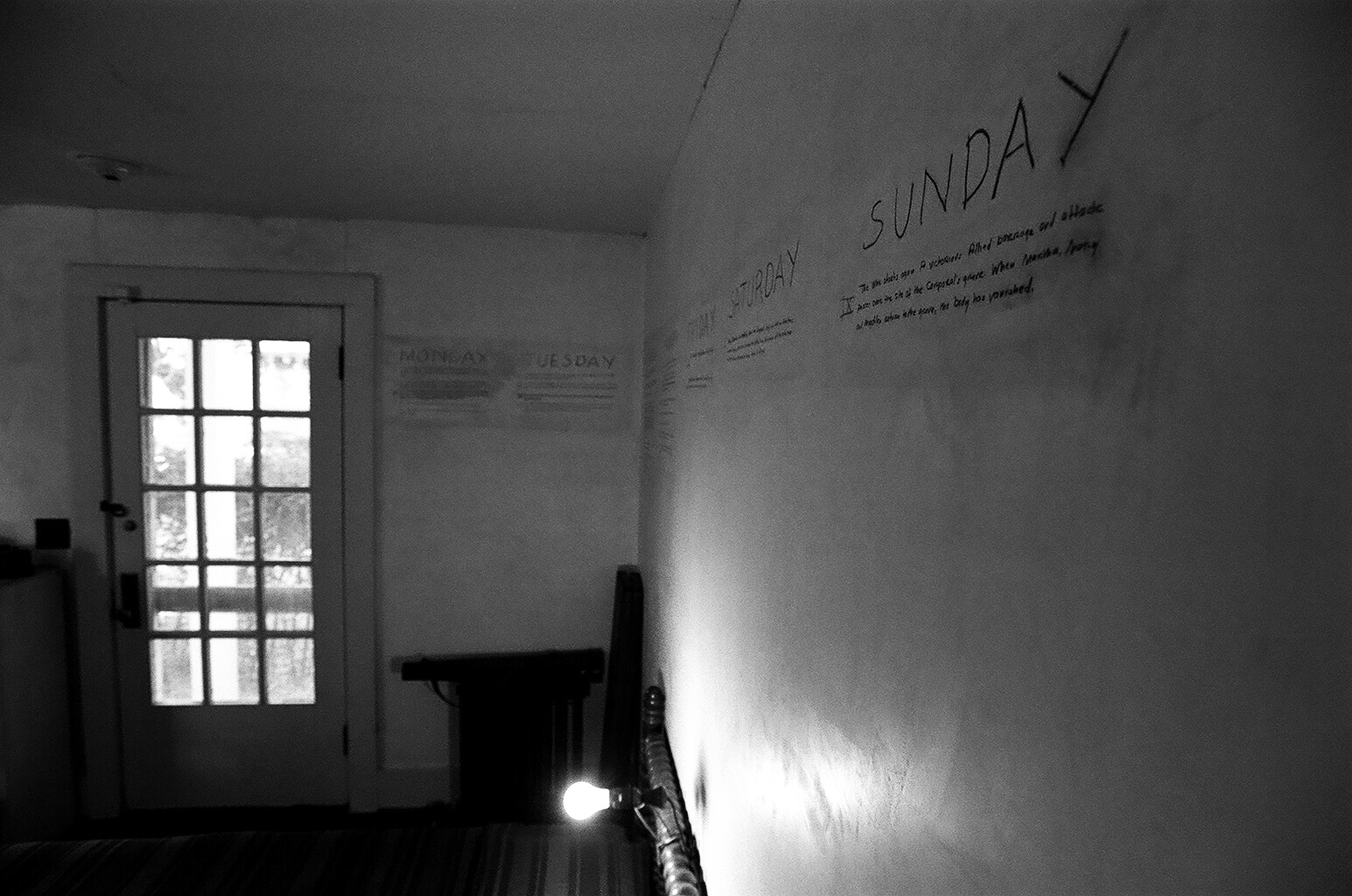

I headed to Bateman’s in Sussex, the Jacobean house where Rudyard Kipling’s elegant desk looked out onto his garden. In Kent, I walked around Sissinghurst Castle Garden and climbed the tower where Vita Sackville-West made her writing room and where she entertained Virginia Woolf. In France, I was smitten with the Château de Cirey where Voltaire wrote and staged short plays in a miniature theater. I roamed around Rowan Oak in Oxford, Mississippi, where William Faulkner turned the walls into his desktop. (He outlined the plot of his novel A Fable on the whitewashed walls of his study).

I always hope that the writing rooms and desktops of such accomplished writers might yield insights into their creative process. That by studying their studies, I could unlock the secret to their literary success. Needless to say, that hope has proven misguided (so far).

But that fascination for workspaces and writing desks is one of the reasons this video essay by Johannes Binotto appeals to me. His Desktop Documentary is a documentary about his desktop and how that flat space both reflects and shapes his intellectual and creative work. It is part of a NECSUS dossier on the desktop documentary format, but Binotto decided to focus on his analog desktop rather than on the digital version that the term refers to. However, the points Binotto makes and the conclusion he arrives at, apply to computer desktops as well.

Johannes Binotto uses his own cluttered work desk as a case study of how that physical environment can facilitate and generate investigative insights. He claims that its messy layout is “literally how it just looked this morning”, but the fact that almost all objects on it come in very handy during his talk raises the suspicion that it might have been slightly staged (*). In true essayistic tradition, Binotto’s monologue meanders via Freud, Lacan, Barthes, and Tati to end up at his own insights into three specific qualities of the physical desktop. He cherishes the spatial limitations of the table he works at. He actively encourages the intermingling of the various objects on it. And finally, he enjoys the aleatory connections (“productive accidents” he calls them) that emerge from the academic flotsam and jetsam that wash up on his desk.

The reason I haven’t learnt much from all those writers’ studies I visited over the years is that they had been too carefully reconstructed. Rather than offering a glimpse into the psyche of the writer they only taught me that museum curators and set dressers think alike: they stage things a little too neatly. They impose the orderly logic of an exhibit on the messiness of the mind, and in doing so sacrifice truthfulness for clarity. Binotto’s wonderful video essay makes a case for chaos and for the opportunities it brings.